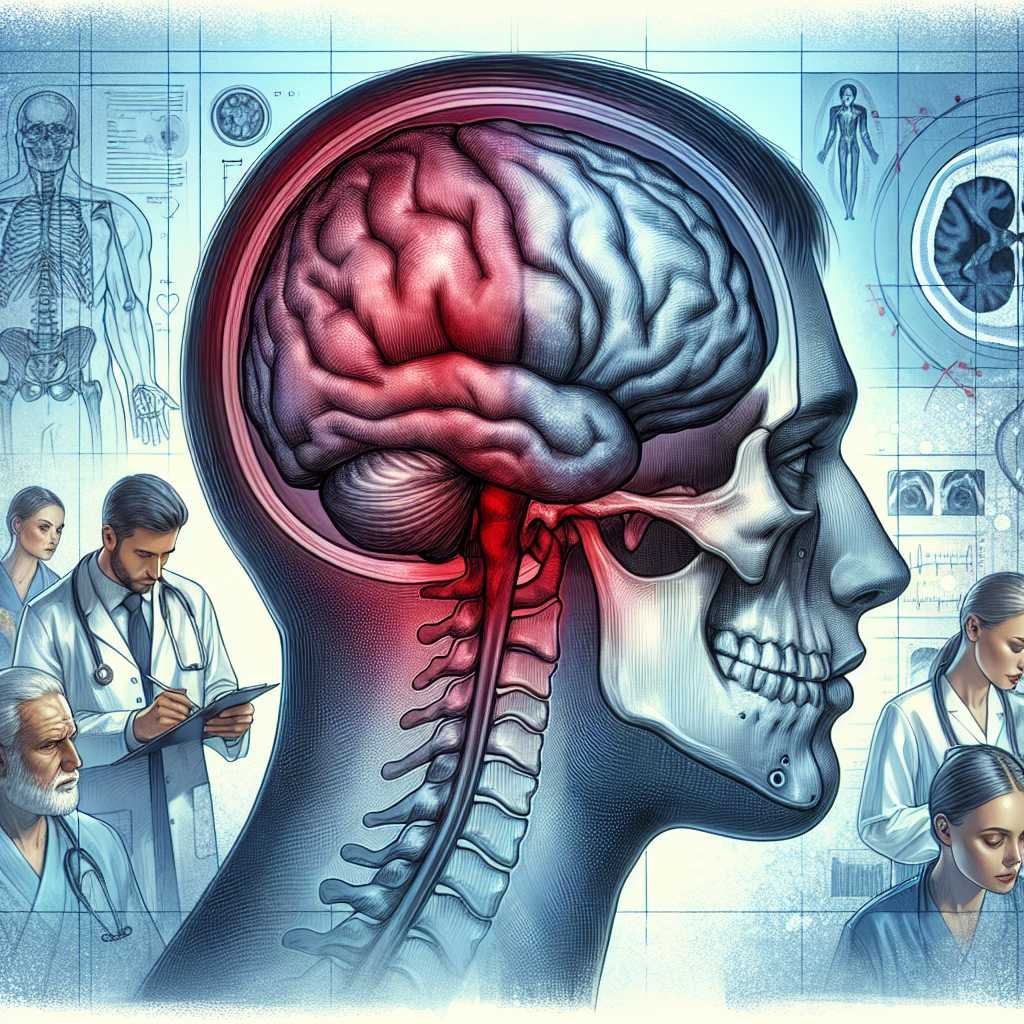

During the Clinical evaluation of subjects with a recent history of head trauma is possible to find one or more of the following clinical signs: unilateral or bilateral blepharo-hematoma, blood otorrhea, rhinorrhea and Battle’s sign (retro-auricular ecchymosis). These clinical signs in the diagnosis of basilar skull fracture (BSF) are ambiguous, but widely used to make decisions about initial interventions involving traumatized patients (1).

History and Meaning

Battle’s sign is defined as bruising in the retro-auricular or mastoid region following a head injury and is a clinical indicator of fracture in the posterior cranial fossa of the base of the skull.Its name derives from that of the English surgeon William Henry Battle (1855-1936) who described it in a series of cases about 130 years ago (2).

Battle’s sign is typically related to blunt head trauma, mostly accidental, but can also be detected in a non-accidental head injury, including child abuse (3).

Its presence has a positive predictive value greater than 75% for the presence of an associated basilar skull fracture and 66% for intracranial lesions (3).

Skull base fractures

Most BSFs are caused by high-speed blunt trauma such as motor vehicle collisions, motorcycle accidents, and pedestrian injuries. Falls and assaults are also important causes (4).

BSFs are relatively rare and are present in approximately 4% of all patients with severe head injury and account for 19% to 21% of skull fractures.At least 50% of BSF is associated with another lesion of the central nervous system (5). Most BSFs involve the petrous bone, the external ear canal and the tympanic membrane. Data reveal that 15% of patients with BSF have an associated lesion of the cervical spine (5). When patients present with Battle’s sign, it is essential to exclude associated cervical spine lesions as well.

Battle sign and severity of trauma

The verification of the correlation between the presence of Battle’s sign (and other clinical signs) with the severity of head trauma was analyzed in a prospectively designed follow-up study performed with structured observations for 48 hours in post-blunt head trauma in patients aged > 12 years (3). In addition to Battle’s sign, the following signs of BSF were considered: blepharo-hematoma, otorrhea and rhinorrhea. Of 136 patients enrolled (85.3% males; mean age 40 ± 21.4 years), 28 patients (20.6%) had BSF. I clinical signs for early or late detection of BSF had low accuracy (55.9% vs.43.4%), specificity (52.8% vs. 30.5%) and positive predictive value (25.7% vs. 27.1%). However, the presence of these signs correlated with the severity of the head injury, as measured by the Glasgow Coma Scale (p = .041).

In summary – The performance of the Battle sign (within 48 hours after trauma) for the diagnosis of BSF has a good correlation with the severity of a head injury assessed according to Glasgow Coma Scale (1).

Therefore, the visual acknowledgment of the Battle sign on physical examination does not require further evaluation to be confirmed and, considering its correlation with a BSF, places the indication for the study of imaging with CT without contrast and subsequent management procedures in a specialized hospital setting.

Access to the site is restricted and reserved for healthcare professionals

You have reached the maximum number of visits

Source – https://www.univadis.it/viewarticle/trauma-cranico-l-importanza-del-segno-di-battle-2023a1000019