Introduction

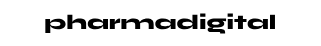

Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MASLD) and Diabetes Mellitus are two prevalent metabolic disorders that often coexist and synergistically contribute to the progression of each other. Several pathophysiological pathways are involved in the association, including insulin resistance, inflammation, and lipotoxicity, providing a foundation for understanding the complex interrelationships between these conditions. The presence of MASLD significantly impacts diabetes risk and the development of microvascular and macrovascular complications, while diabetes significantly contributes to an increased risk of liver fibrosis progression in MASLD and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Moreover, both pathologies have a synergistic effect on cardiovascular events and mortality.

Pathogenic Pathways Involved in the Synergic Interaction

Insulin Resistance, Liver Lipotoxicity, and Adipocyte Dysfunction

Insulin resistance is the main driver for MASLD and T2DM. Its presence is sine qua non for both diseases. In the liver, insulin resistance is mainly manifested by disrupted regulation of glucose metabolic pathways, such as increased neo-glucogenesis and glycogenolysis and decreased glycogen synthesis. As a direct consequence, hyperglycemia develops, and pancreatic β cells respond by increasing insulin secretion to maintain glycemic control.

In skeletal muscle, one of the main organs involved in glucose consumption, insulin response is dysregulated, reducing glucose transport and glycogen synthesis in myocytes. This metabolic derangement induces a chronic state of hyperinsulinemia that, in the long term, cannot sustain normoglycemia, leading to T2DM. Insulin resistance in peripheral adipose tissue increases lipolysis and free fatty acid production, which are avidly captured by hepatocytes. In the liver, lipid metabolic pathways such as sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) and carbohydrate regulatory element-binding protein (ChREBP) are enhanced by hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia, respectively, inducing dysregulated enhanced lipogenesis and liver steatosis.

Microbiota Dysbiosis

Microbiota is another important element in metabolic dysfunction. Intestinal flora (including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa) closely interact with intestinal cells through several receptors, including toll-like receptors (TLRs) and intranuclear-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (or NOD-like receptors). Microorganisms’ products (e.g., lipopolysaccharides, DNA, peptidoglycans) penetrate through the gastrointestinal barrier and directly interact with liver cells, including hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, sinusoidal cells, and dendritic cells, among others.

MASLD is characterized by several microbiota changes (dysbiosis) associated with increased intestinal permeability that promote MASLD progression. MASLD patients have lower proportions of Bacteroidetes and higher proportions of Prevotella and Porphyromonas spp. This dysbiotic phenotype is also present in T2DM. Ethanol-producing bacteria such as E. coli and Klebsiella are also increased in subjects with NASH, and this is associated with increased blood concentration of alcohol. Other relevant pathogenic bacterial metabolites have been described to be involved in MASLD pathogenesis, such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO).

Clinical Implications of the MASLD and T2DM Association

Surveillance, Diagnosis, and Staging

Clinicians should be aware of the consequences of the symbiotic association between T2DM and MASLD. Due to the high prevalence and multisystemic implications, their management should not be restricted to liver specialists; on the contrary, it should be expanded to general practitioners, internal medicine, cardiologists, diabetologists, and endocrinologists, among other specialties. The clinical implications of this relation will be detailed in the following sections.

Importance of T2DM Surveillance in MASLD Patients

Because of the 2-3-fold increased risk of diabetes incidence in MASLD patients, most guidelines recommend screening T2DM in MASLD patients. Active surveillance with serum fasting glucose and HbA1c should be included for MASLD patients. Since MASLD is a strong risk factor for T2DM, we recommend screening every 1-2 years, particularly in obese subjects or subjects with a family history of T2DM.

T2DM diagnosis has implications for liver fibrosis progression in MASLD and the risk of HCC. In a meta-analysis of 6 retrospective cohort studies (n=2016), with a median follow-up of 2.8 years, the presence of T2DM in MASLD patients increased the risk of hepatic decompensation (defined as the presence of ascites, encephalopathy, or variceal bleeding) with an adjusted HR=2.14 (95% CI=1.4−3.3). This result remained significant in the subgroup analysis of patients without cirrhosis (HR=2.5, P=0.03). In subjects with MASLD cirrhosis, T2DM represents a significant risk factor for HCC, with an HR=5.25 (95% CI=1.1−24.7).

MASLD and Microvascular Complications of T2DM

The presence of MASLD is associated with an increased risk of microvascular complications of T2DM, in particular, renal failure and diabetic neuropathy. Regarding chronic kidney disease (CKD), a recent meta-analysis of 13 observational studies with a median follow-up of 9.7 years estimated an increased risk of CKD defined as glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 in subjects with MASLD (HR=1.43; 95% CI 1.33−1.54). The risk of CKD is likely to be increased in advanced liver fibrosis with HR 2.8−3.3 in subjects with histology confirmed ≥F3.

There is also evidence about the association between MASLD and diabetic neuropathy. A recent prospective, case-control study (case n=1208; control n=1908) with a median follow-up of 5 years demonstrated an increased risk of neuropathy in MASLD subjects with an OR: 1.34 (95% CI: 1.1−1.6). The association between MASLD and retinopathy lacks clarity. A recent meta-analysis concluded no significant association between these entities (OR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.7−1.3).

Therapeutic Interventions for T2DM and MASLD

Lifestyle Interventions

Lifestyle intervention is the mainstay treatment for T2DM and MASLD. Obesity is one of the major drivers of the pathogenesis of both diseases. Hence, weight loss is the main aim of overweight and obese patients. A weight reduction of >7% is associated with MASH resolution in 64%, and >10% decreased weight is associated with MASH resolution in 90% and liver fibrosis regression in 81% of subjects. Weight loss induces better metabolic control of T2DM.

Regarding macronutrient composition, carbohydrate restriction is needed for metabolic control in diabetes and can help to reduce body weight. The Mediterranean diet is the preferred recommendation because of solid evidence on the reduction of diseases associated with MASLD and T2DM, such as cardiovascular events, stroke, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality. Evidence on other types of diet, such as intermittent fasting or ketogenic diet, is based only on short-term studies with variable results; they are recommended in specific patients supervised by dietitians.

Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

To prevent cardiovascular events is a major significant target for treating subjects with T2DM. Controlling the multiple CVD risk factors associated with T2DM and MASLD (blood pressure, HbA1c, blood cholesterol, smoking) is of significant importance since it can reduce CV events by approximately 62%. Aggressive treatment of hypertension and dyslipidemia is recommended. Hypertension medication should target blood pressure <130/80 mmHg; however, this target should be adapted individually and a higher target should be considered in elderly or fragile patients.

Management of blood cholesterol should be customized according to the patient’s estimated CV risk. Statins are first-line therapy and are safe to use in subjects with MASLD. US guidelines recommend that all subjects with T2DM between 40 and 75 years old should be considered to start statin therapy at moderate intensity (LDL reduction of 30−50%). Clinical guidelines of the American Associations of Endocrinology and Hepatology (AACE and AASLD) recommend that subjects with T2DM and MASLD without other CV risk factors should target LDL <100 mg/dL. High-intensity statin therapy and ezetimibe aimed to reduce LDL cholesterol by ≥50% should be started in subjects with multiple risk factors or 10-year estimated risk estimated ≥20% assessed by ASCVD risk estimator plus.

Bariatric Surgery

In patients with obesity and T2DM or high-risk MASLD, bariatric surgery can induce sustained, major weight loss. The metabolic effects of this type of surgery significantly improve glycemic control in T2DM patients. The long-term effects of bariatric surgery in MASLD were described in a prospective study open-label French study of subjects with MASLD undergoing bariatric surgery with follow-up biopsies at 1 and 5 years. At 5-year MASH was resolved in 84%, fibrosis decreased in 70% of patients. Fibrosis reduction is progressive, beginning during the first year and continuing through 5 years.

A recent randomized controlled trial was conducted in 431 subjects with biopsy-proven MASH. They were randomized 1:1:1 to lifestyle modification plus best medical care, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, or sleeve gastrectomy and followed for one year. The probability of MASH resolution was 3.6 times greater (95% CI 2.19−5.92; p<0.0001) in the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass group and 3.7 times greater (2.23−6.02; p<0.0001) in the sleeve gastrectomy group compared with in the lifestyle modification group. These data strongly support the beneficial effects of bariatric-metabolic surgery in subjects with T2DM and MASLD.

Pharmacologic Treatment for MASLD

At present, no medication for MASLD has been recommended specifically for MASLD therapy, although some medications have been studied in randomized controlled trials. In a three-arm RCT that compared Vitamin E, pioglitazone, and placebo, vitamin E (800 UI per day for 96 weeks) was demonstrated to improve histology (reduction of NAS>2 points) compared to placebo in the PIVENS trial. This study excluded patients with diabetes, and there was no effect on liver fibrosis. There are no prospective long-term studies with vitamin E and there is some concern about adverse effects, including increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke and prostate cancer. There is scarce evidence to support its use in MASLD and T2DM populations.

Pharmacologic Treatment for T2DM in Patients with MASLD

Patients with T2DM can benefit from medications that can potentially have positive effects on MASLD and liver disease. Metformin is the first-line pharmacologic therapy for T2DM; however, a direct effect on MASLD histology has not been demonstrated. Metformin can be safely used in compensated cirrhosis and can potentially reduce HCC incidence. Pioglitazone has been demonstrated to increase MASH resolution (OR=3.22; 95% CI 2.17−4.79) and reduce fibrosis progression (OR=1.66; 95% CI 1.12−2.47) in subjects with MASLD and T2DM or prediabetes.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA) has beneficial effects like weight loss and cardiovascular risk reduction in diabetic patients. In addition, two RCTs have demonstrated significant effects of GLP-1RA in histologic outcomes of MASLD. A preliminary small study with liraglutide (1.8 mg/d for 48 weeks) in a small RCT of 52 patients was demonstrated to significantly increase MASH resolution (39 % vs. 9 %, P=0.02) and reduce fibrosis progression (9% vs. 36%, P=0.04) compared to placebo. A second phase 2 RCT was conducted with semaglutide in daily dose for 72 weeks in subjects with biopsy-proven MASH. Resolution of steatohepatitis was achieved in 59% at the higher dose (equivalent to 2.4 mg/week semaglutide) compared with 17% in the placebo group (P < 0.001). No significant reduction of fibrosis was observed. However, fibrosis progression was significantly reduced (59% vs. 17%, P<0.001) for the high-dose group.

Currently, there is an ongoing phase 3 trial for 5-year therapy with semaglutide in subjects with MASLD and F2-3 stage of fibrosis. Based on this data, current ADA guidelines published in 2023 have recommended GLP-1 RA or pioglitazone as the preferred agents for the treatment of hyperglycemia in adults with T2DM biopsy-proven non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, or those at high risk for MASLD with clinically significant liver fibrosis using non-invasive tests.

Conclusion

This review illuminates the intricate relationship between T2DM and MASLD, detailing their shared pathophysiological mechanisms and the mutual impact on each other’s progression. The coexistence of these conditions poses significant challenges in patient management, emphasizing the need for integrated approaches.

The intricate interplay of insulin resistance, inflammation, and hepatic lipid metabolism serves as a key nexus linking T2DM and MASLD. Lifestyle modifications, including weight management and physical activity, emerge as central pillars in the prevention and management of both conditions. GLP-1 RA and pioglitazone therapy have been included in recent guidelines for the treatment of T2DM subjects with MASLD. Aggressive CVD risk factors management is necessary to reduce mortality. Furthermore, advancements in pharmacological interventions hold promise in addressing the complex metabolic pathways involved.

As research continues to unveil the molecular intricacies of T2DM and MASLD, therapeutic strategies need to evolve, focusing on personalized approaches that consider the overlapping components of these diseases and their extra-hepatic complications. A holistic understanding of the connections between T2DM and MASLD is pivotal for devising effective interventions that improve patient outcomes and reduce the global burden of these metabolic disorders.

References

- Arab JP, Arrese M, Trauner M. Recent insights into the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Annu Rev Pathol 2018;13:321–50.

- GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023;402:203–34.

- Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, Underwood FE, King JA, Afshar EE, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:851–61.

- Younossi Z, Tacke F, Arrese M, Chander Sharma B, Mostafa I, Bugianesi E, et al. Global perspectives on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2019;69:2672–82.

- Allen AM, Lazarus JV, Younossi ZM. Healthcare and socioeconomic costs of NAFLD: A global framework to navigate the uncertainties. J Hepatol 2023;79:209–17.