Introduction

Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MASLD) and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) are two prevalent metabolic disorders that often coexist and exacerbate each other’s progression. This article explores the complex interrelationship between these conditions, highlighting the pathophysiological pathways involved, the clinical implications, and potential therapeutic interventions.

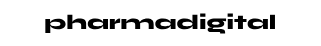

The Intertwined MASLD and T2DM Relationship

MASLD is characterized by liver macrosteatosis in more than 5% of hepatocytes, often associated with insulin resistance conditions such as obesity, T2DM, and metabolic syndrome. While MASLD frequently presents as a mild disease, it can progress to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) in 20-25% of cases, leading to liver cirrhosis and increased liver-related mortality.

T2DM and MASLD are global health concerns with significant public health burdens. The prevalence of T2DM is expected to rise from 529 million individuals in 2021 to 1.23 billion by 2050. Similarly, MASLD is one of the most common causes of liver disease worldwide, with a prevalence increase from 25.5% before 2005 to 37.8% in recent years.

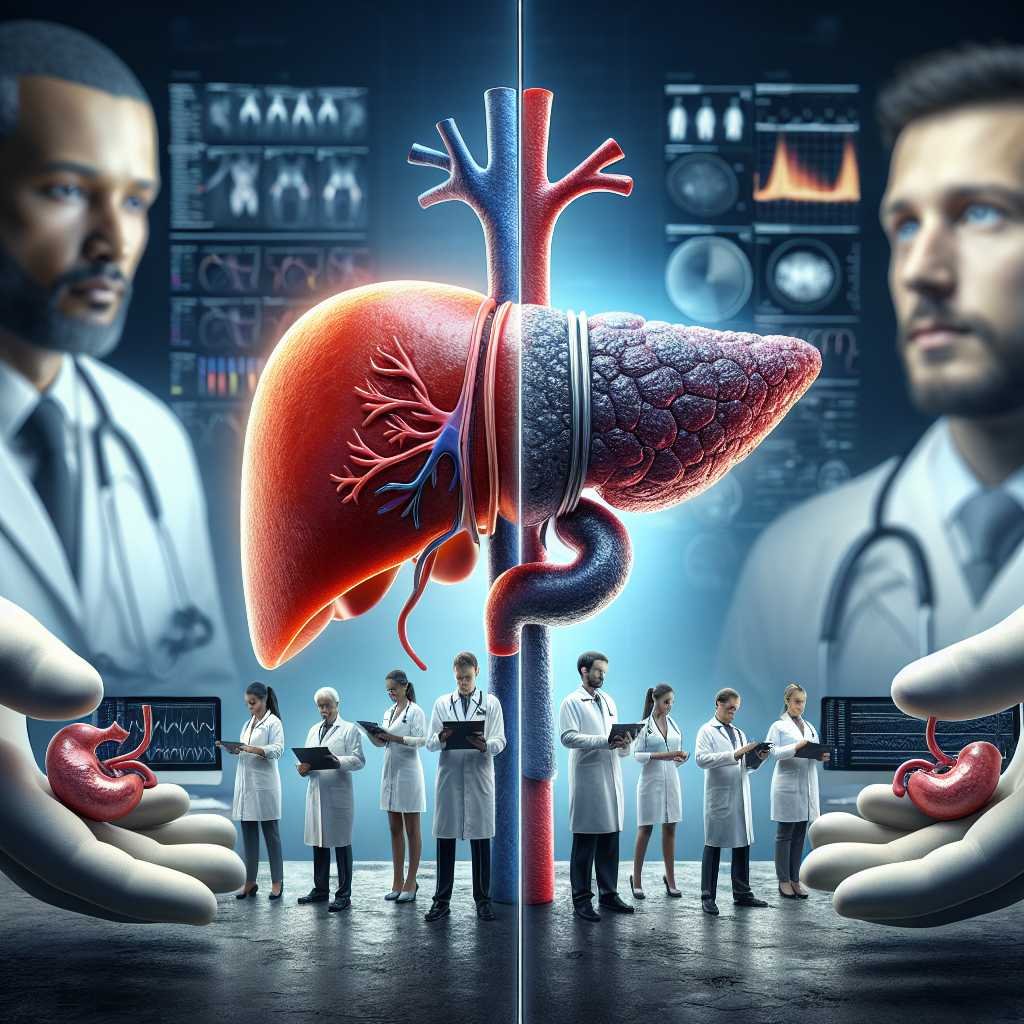

Pathogenic Pathways Involved in the Synergic Interaction

Insulin Resistance, Liver Lipotoxicity, and Adipocyte Dysfunction

Insulin resistance is a key driver for both MASLD and T2DM. In the liver, it disrupts glucose metabolic pathways, leading to hyperglycemia and increased insulin secretion. This metabolic derangement induces chronic hyperinsulinemia, contributing to T2DM development. In peripheral adipose tissue, insulin resistance increases lipolysis and free fatty acid production, which are captured by hepatocytes, leading to liver steatosis and lipotoxicity.

Microbiota Dysbiosis

Microbiota dysbiosis plays a significant role in metabolic dysfunction. Changes in intestinal flora promote MASLD progression by increasing intestinal permeability and interacting with liver cells. Dysbiosis is also present in T2DM, contributing to systemic inflammation and increased risk of MASLD and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Bile Acid Metabolic Pathways

Bile acid signaling, involving receptors like FXR and TGR5, regulates glucose and lipid metabolism. FXR activation reduces lipogenesis and increases fatty acid oxidation, while TGR5 activation promotes insulin secretion and increases energy expenditure. Modifications in bile acid metabolism are observed in MASH, independent of obesity and T2DM.

Genetic Factors for MASLD and T2DM

Genetic predisposition plays a role in both T2DM and MASLD. Variants influencing insulin production, insulin resistance, and adiposity are linked to T2DM. For MASLD, genetic variants involved in lipid processing and hepatocyte function contribute to disease progression and increased hepatic insulin resistance.

Clinical Implications of the MASLD and T2DM Association

Surveillance, Diagnosis, and Staging

Due to the high prevalence and multisystemic implications, managing MASLD and T2DM requires a multidisciplinary approach. Regular screening for T2DM in MASLD patients and vice versa is recommended. Liver function tests alone are insufficient for MASLD assessment; non-invasive tests (NITs) like FIB-4 and imaging-based elastography are essential for evaluating liver fibrosis.

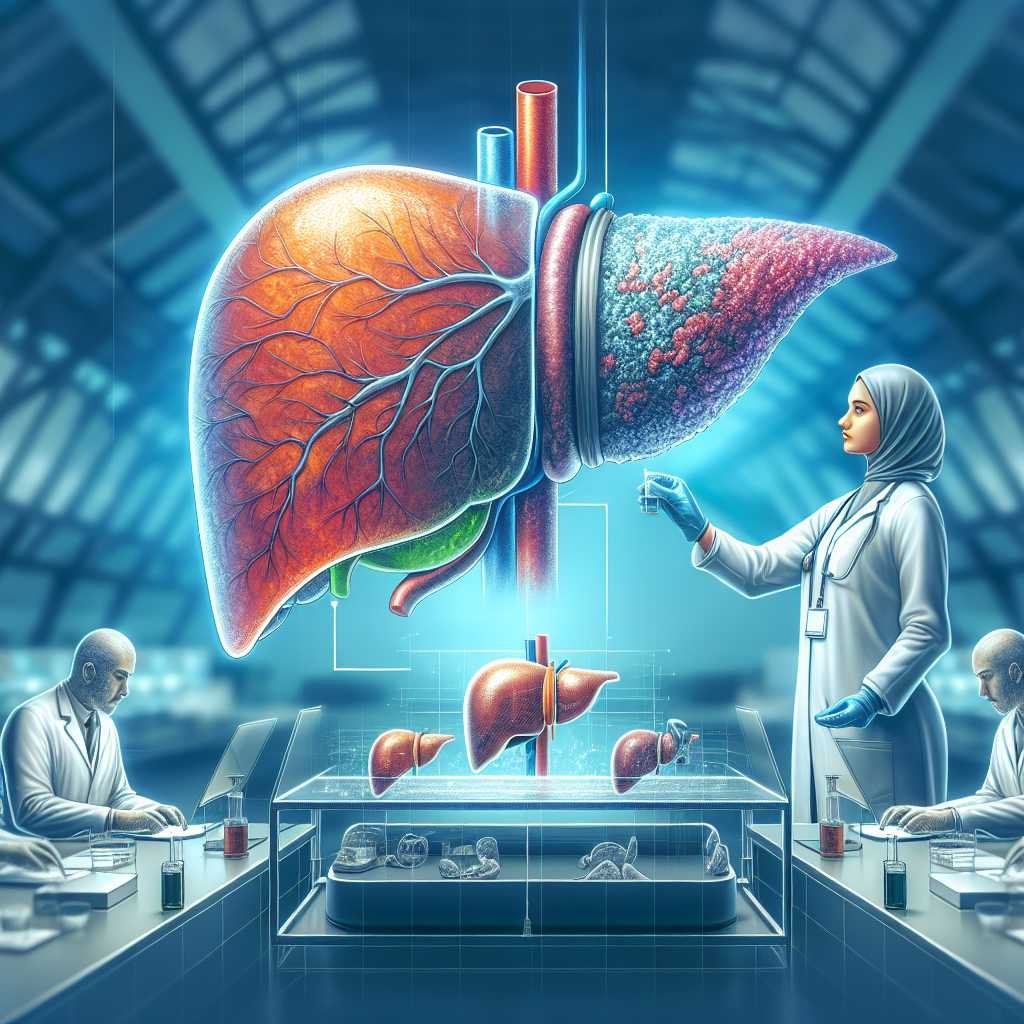

Importance of T2DM Surveillance in MASLD Patients

MASLD patients have a 2-3 fold increased risk of developing T2DM. Regular screening with fasting glucose and HbA1c is recommended, especially in obese individuals or those with a family history of T2DM. T2DM diagnosis impacts liver fibrosis progression and the risk of HCC in MASLD patients.

MASLD and Microvascular Complications of T2DM

MASLD increases the risk of microvascular complications in T2DM, particularly chronic kidney disease (CKD) and diabetic neuropathy. The presence of MASLD is associated with a higher risk of CKD and neuropathy, necessitating vigilant monitoring and management.

Cardiovascular Disease in Subjects with T2DM and MASLD

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in T2DM and MASLD. Both conditions independently increase the risk of coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and heart failure. Managing associated risk factors is crucial to prevent CVD in patients with combined T2DM and MASLD.

Surveillance of MASLD and Liver Complications in Patients with T2DM

MASLD assessment in T2DM patients is recommended in most guidelines. Diagnosis involves detecting liver steatosis, ruling out other causes, and assessing liver fibrosis severity using NITs. Regular monitoring and appropriate management of liver complications are essential for improving patient outcomes.

Therapeutic Interventions for T2DM and MASLD

Lifestyle Interventions

Weight loss through lifestyle modifications is the cornerstone of treatment for both T2DM and MASLD. A weight reduction of more than 7% is associated with significant improvements in MASH and liver fibrosis. The Mediterranean diet and regular exercise are recommended for their beneficial effects on metabolic control and cardiovascular health.

Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

Preventing cardiovascular events is a major goal in treating T2DM and MASLD. Aggressive management of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and other CVD risk factors is essential. Statins are recommended for cholesterol management, and antiplatelet therapy may be considered for primary prevention in high-risk patients.

Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric surgery is an effective intervention for patients with obesity and T2DM or high-risk MASLD. It induces significant weight loss, improves glycemic control, and resolves MASH in a substantial proportion of patients. Careful selection and multidisciplinary care are crucial for optimal outcomes.

Pharmacologic Treatment for MASLD

Currently, no specific medication is recommended for MASLD therapy, although several drugs are under investigation. Vitamin E and pioglitazone have shown some benefits in clinical trials, but further research is needed to establish their long-term efficacy and safety.

Pharmacologic Treatment for T2DM in Patients with MASLD

Medications like GLP-1 receptor agonists and pioglitazone have shown promise in treating T2DM and MASLD. These drugs improve glycemic control, promote weight loss, and have beneficial effects on liver histology. Recent guidelines recommend their use in T2DM patients with MASLD.

Conclusion

The intricate relationship between T2DM and MASLD necessitates integrated management approaches. Understanding the shared pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical implications is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies. Lifestyle modifications, pharmacologic interventions, and regular monitoring are essential for improving patient outcomes and reducing the global burden of these metabolic disorders.

Authors

Francisco Barrera, Javier Uribe, Nixa Olvares, Paula Huerta, Daniel Cabrera, Manuel Romero-Gomez

References

[1] Arab JP, Arrese M, Trauner M. Recent insights into the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Annu Rev Pathol 2018;13:321–50.

[2] GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023;402:203–34.

[3] Gallardo-Rincón H, Cantoral A, Arrieta A, Espinal C, Magnus MH, Palacios C, et al. Review: type 2 diabetes in Latin America and the Caribbean: regional and country comparison on prevalence, trends, costs and expanded prevention. Prim Care Diabetes 2021;15:352–9.

[4] Diabetes prevalence (% of population ages 20 to 79) – Latin America & Caribbean. World Bank Open Data n.d. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.DIAB.ZS?locations=ZJ (accessed 13 January 2024).

[5] Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, Underwood FE, King JA, Afshar EE, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:851–61.

[6] Younossi Z, Tacke F, Arrese M, Chander Sharma B, Mostafa I, Bugianesi E, et al. Global perspectives on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2019;69:2672–82.

[7] Díaz LA, Ayares G, Arnold J, Idalsoaga F, Corsi O, Arrese M, et al. Liver diseases in Latin America: current status, unmet needs, and opportunities for improvement. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2022;20:261–78.

[8] Allen AM, Lazarus JV, Younossi ZM. Healthcare and socioeconomic costs of NAFLD: A global framework to navigate the uncertainties. J Hepatol 2023;79:209–17.

[9] En Li Cho E, Ang CZ, Quek J, Fu CE, Lim LKE, Heng ZEQ, et al. Global prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2023;72:2138–48.

[10] Younossi ZM, Golabi P, de Avila L, Paik JM, Srishord M, Fukui N, et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol 2019;71:793–801.

[11] Ajmera V, Cepin S, Tesfai K, Hoflich H, Cadman K, Lopez S, et al. A prospective study on the prevalence of NAFLD, advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in people with type 2 diabetes. J Hepatol 2023;78:471–8.

[12] Mantovani A, Petracca G, Beatrice G, Tilg H, Byrne CD, Targher G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident diabetes mellitus: an updated meta-analysis of 501 022 adult individuals. Gut 2021;70:962–9.

[13] Targher G, Tilg H, Byrne CD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a multisystem disease requiring a multidisciplinary and holistic approach. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;6:578–88.

[14] Mantovani A, Csermely A, Petracca G, Beatrice G, Corey KE, Simon TG, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;6:903–13.

[15] Loomba R, Friedman SL, Shulman GI. Mechanisms and disease consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell 2021;184:2537–64.

[16] Friedman SL, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Rinella M, Sanyal AJ. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med 2018;24:908–22.

[17] Kawai T, Autieri MV, Scalia R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2021;320:C375–91.

[18] Wolfs MGM, Gruben N, Rensen SS, Verdam FJ, Greve JW, Driessen A, et al. Determining the association between adipokine expression in multiple tissues and phenotypic features of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obesity. Nutr Diabetes 2015;5:e146.

[19] Kucukoglu O, Sowa J-P, Mazzolini GD, Syn W-K, Canbay A. Hepatokines and adipokines in NASH-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2021;74:442–57.

[20] Dunmore SJ, Brown JEP. The role of adipokines in b-cell failure of type 2 diabetes. J Endocrinol 2013;216:T37–45.

[21] Albhaisi SAM, Bajaj JS. The influence of the microbiome on NAFLD and NASH. Clin Liver Dis 2021;17:15–8.

[22] Gurung M, Li Z, You H, Rodrigues R, Jump DB, Morgun A, et al. Role of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. EBioMedicine 2020;51:102590.

[23] Yuan J, Chen C, Cui J, Lu J, Yan C, Wei X, et al. Fatty liver disease caused by high-alcohol-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell Metab 2019;30 675−88.e7.

[24] Theofilis P, Vordoni A, Kalaitzidis RG. Trimethylamine N-oxide levels in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolites 2022;12.

[25] Ponziani FR, Bhoori S, Castelli C, Putignani L, Rivoltini L, Del Chierico F, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with gut microbiota profile and inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2019;69:107–20.

[26] Trebicka J, Macnaughtan J, Schnabl B, Shawcross DL, Bajaj JS. The microbiota in cirrhosis and its role in hepatic decompensation. J Hepatol 2021;75(Suppl 1):S67–81.

[27] Arab JP, Karpen SJ, Dawson PA, Arrese M, Trauner M. Bile acids and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: molecular insights and therapeutic perspectives. Hepatology 2017;65:350–62.

[28] Jiao T-Y, Ma Y-D, Guo X-Z, Ye Y-F, Xie C. Bile acid and receptors: biology and drug discovery for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2022;43:1103–19.

[29] Ding L, Sousa KM, Jin L, Dong B, Kim B-W, Ramirez R, et al. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy activates GPBAR-1/TGR5 to sustain weight loss, improve fatty liver, and remit insulin resistance in mice. Hepatology 2016;64:760–73.

[30] Perino A, Velázquez-Villegas LA, Bresciani N, Sun Y, Huang Q, Fénelon VS, et al. Central anorexigenic actions of bile acids are mediated by TGR5. Nat Metab 2021;3:595–603.

[31] Wang W, Cheng Z, Wang Y, Dai Y, Zhang X, Hu S. Role of bile acids in bariatric surgery. Front Physiol 2019;10:374.

[32] Sirdah MM, Reading NS. Genetic predisposition in type 2 diabetes: a promising approach toward a personalized management of diabetes. Clin Genet 2020;98:525–47.

[33] Trépo E, Valenti L. Update on NAFLD genetics: from new variants to the clinic. J Hepatol 2020;72:1196–209.

[34] Targher G, Corey KE, Byrne CD, Roden M. The complex link between NAFLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus – mechanisms and treatments. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;18:599–612.

[35] Huang DQ, Noureddin N, Ajmera V, Amangurbanova M, Bettencourt R, Truong E, et al. Type 2 diabetes, hepatic decompensation, and hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an individual participant-level data meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;8:829–36.

[36] Alexopoulos A-S, Crowley MJ, Wang Y, Moylan CA, Guy CD, Henao R, et al. Glycemic control predicts severity of hepatocyte ballooning and hepatic fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2021;74:1220–33.

[37] Allen AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. The Importance of glycemic equipoise in NASH. Hepatology 2021;74:1145–7.

[38] Mantovani A, Petracca G, Beatrice G, Csermely A, Lonardo A, Schattenberg JM, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident chronic kidney disease: an updated meta-analysis. Gut 2022;71:156–62.

[39] Mantovani A, Zaza G, Byrne CD, Lonardo A, Zoppini G, Bonora E, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease increases risk of incident chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism 2018;79:64–76.

[40] Mantovani A, Taliento A, Zusi C, Baselli G, Prati D, Granata S, et al. PNPLA3 I148M gene variant and chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetic patients with NAFLD: clinical and experimental findings. Liver Int 2020;40:1130–41.

[41